Sustainable tourism – justice, green transition and cultural tourism were the main topics for TourNord’s 6th network meeting in Kalmar, Sweden. Hosted by the Linnaeus University and Associate Professor Marianna Strzelecka, the network meeting served as a forum for exchanging best practices and experiences for education and knowledge development within Nordic Tourism. We were treated to two days of fantastic presentations, discussions and an insight into the coastal community of Kalmar and its neighbouring island, Öland. In true TourNord fashion, the weather also delivered so we were able to see the south-east coast of Sweden at its best!

Day 1: Justice in tourism, co-creation with cultural tourism and excursion to Öland

The beautiful Kalmar Slott set the scene for the first part of our network meet. After a warm welcome from TourNord Project Lead Christian Dragin-Jensen, the group was given a tour around the historic Kalmar Slott. This was then followed by an exciting presentation given by Marianna Strzelecka from Linnaeus University on one of their current research projects.

The project, titled “Energy justice for rural communities – Towards pathways to empowerment in sustainability transitions”, aims to bring justice to the residents of rural areas in sustainable energy transitions. It seeks to provide knowledge about energy injustices by exploring how they are perceived and reproduced in rural settings. As a specific example – if wind turbines are installed in a rural setting – close to houses, communities and/or nature, how can authorities and communities ensure a just distribution of the boons/costs they bring?

A very relevant project when considering the “not in my backyard” mentality that has dominated the energy transition landscape.

Marianna’s presentation was followed by her colleague, Senior Lecturer Per Pettersson-Löfquist, who presented an ongoing project called “Innovative Cultural Entrepreneurship in Collaborative Co-creative Research”. Quite a mouthful of a title, yet Per deftly highlighted several aspects of the larger project, and dove into depth the parts he was directly involved in. More specifically, Per gave a rousing presentation about his work with cultural tourism actors, and how many of these cultural tourism offers are for many tourists the main “reason to go”, but hardly ever the biggest recipients of the income of tourist spend. That is, accommodation and restaurants tend to capture the lion’s share of tourist spending, despite not being the main reason to go. Per went on to show great local examples in the Småland region (of which Kalmar is a part of) on how hotels can collaborate with local glassmakers.

In an age of of co-creation, and with calls for better forms of tourism where we have to look at destinations more holistically, Per’s work certainly brought novel perspectives and food for thought for the TourNord network!

After Per’s presentation, Marianna followed up by sharing their team’s vision for a knowledge environment for sustainable tourism at the Linnaeus University. This was an inspiring presentation on all the processes, politics, and necessary organizational structures needed to create such a knowledge environment at an institution of higher education. There were good lessons for all the TourNord partners who wished to perhaps try the same at their own institutions. This also permitted Marianna to receive feedback from other institutions on how to progress with such a knowledge environment, as well as to extend an invitation to further collaborate on such matters. The discussion also dove into the status of tourism students, the makeup of new study programs and how some schools have tried to tackle the downturn in tourism students. A truly Nordic cooperative meet!

After a wonderful vegetarian lunch at the castle, we were in for a real treat as we were given a tour of Kalmar’s neighbouring island, Öland. The tour was spearheaded by associate professor Ludvig Papmehl-Dufay. Ludvig’s unique knowledge of Öland was not only due to his background as an archaeologist, but also as a resident of the island. Driving around the island, we were treated to insights on the unique flora and fauna of the island, the natural phenonemons such as the Stora Alvaret – a large limestone plain home to many unique and rare species. We were shown how history, nature and tourism interweave on the island, and how the island naturally segments the different types of tourists who arrive (for example – the northern part of the island attracts more ‘traditional’ beach and sun tourists, whereas the southern part attracts more nature-based tourists). We also had an in-prompt discussion on the island’s untapped potential (and pitfalls!) of surf-tourism!

We also visited several farm shops (a unique and critical component of tourism localness in the Småland region), as well as the famous Station Linné, home to world-leading research on flowers, insects and Alvaret’s nature.

Day 2: Workshop, TourNord business, and tour of Kalmar oldtown

After a good’s night rest, we started out bright and early at the beautiful Linneus University campus. As this was our 6th and last Nordplus financed network meet, we needed to discuss how we wished to continue with TourNord – and in what format.

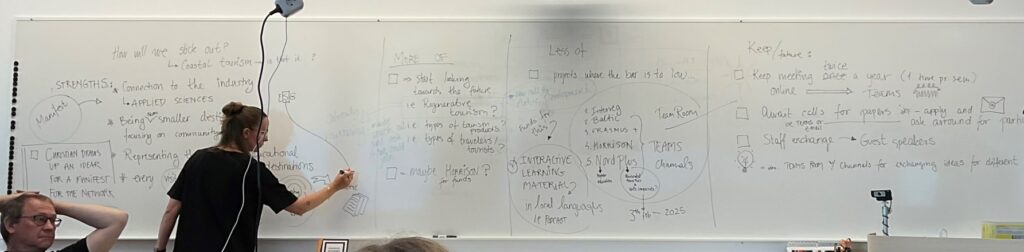

A workshop was held on how we wished to structure TourNord going forward, with the following decisions being made:

- We still wish to meet physically and will pursue funds on how to do so. Until funds are secured, we will meet as a minimum twice a year (1x per semester) online, or more often if needed.

- Microsoft teams channels will be created, with each channel serving a different function (general communication, different funding possibilities, staff exchange, etc.) to streamline our different acitivities

- All team members will be proactive in looking at different calls for projects that are of relevance to TourNord institutions

- Christian Dragin-Jensen will continue as Project Lead

Christian Dragin-Jensen and Ove Oklevik were also able to present the manuscript of TourNord’s upcoming book “Nordic Coastal Tourism – Sustainability, Trends, Practices and Opportunities”. The book is in its final stages at the publisher and we are hoping that the book will be ready for its release by the end of the year!

The book has been the brainchild of the TourNord network and editors Christian Dragin-Jensen, Grzegorz Kwiatkowski and Ove Oklevik applauded all the hard work done by all the Tournord members and other authors of the chapters for making this book a reality!

The TourNord network also agreed to look into further funding possibilities for science communication regarding the publishing of the book, as well as creating teaching material regarding the book.

With the workshop and Tournord business settled, we were given a tour of the beautiful and historic old town of Kalmar, followed by a lunch.

All the participating TourNord members would like to thank Linnaues University and its partners for their warm hospitality, and a fantastic program which ensured that our network meet serve:

1. As a forum for exchanging best practices and experiences for education and knowledge development within Nordic Tourism

2. To discover and implement innovative ways of teaching to benefit educators and students in preparing them for the current/future demands of Nordic Tourism

3. To promote & advance student/staff mobility amongst partners for learning, innovation and R&D activities within NT.